NHIS Example

The tutorial aims to guide the users through fitting machine learning (ML) techniques with health survey data. We will use the National Health Interview Survey (NHIS) 2016 dataset to develop prediction models for predicting high impact chronic pain (HICP) among adults aged 65 years or older. We will use LASSO and random forest models with sampling weights to obtain population-level predictions. In this tutorial, the split-sample approach as an internal validation technique will be used. You can review the earlier tutorial on data splitting technique. Note that this split-sample approach is flagged as a problematic approach in the literature (Steyerberg et al. 2001). The better approach could be cross-validation and bootstrapping Steyerberg and Steyerberg (2019). In the next tutorial, we will apply the ML techniques for survey data with cross-validation.

Steyerberg EW, Harrell Jr FE, Borsboom GJ, Eijkemans MJ, Vergouwe Y, Habbema JD. Internal validation of predictive models: efficiency of some procedures for logistic regression analysis. Journal of Clinical Epidemiology. 2001; 54(8):774-81. DOI: 10.1016/S0895-4356(01)00341-9

Steyerberg EW, Steyerberg EW. Overfitting and optimism in prediction models. Clinical prediction models: A practical approach to development, validation, and updating. 2019:95-112. DOI: 10.1007/978-3-030-16399-0_5

For those interested in the National Health Interview Survey (NHIS) dataset, can review the earlier tutorial about the dataset.

Load packages

We load several R packages required for fitting LASSO and random forest models.

Analytic dataset

Load

We load the dataset into the R environment and lists all available variables and objects.

The dataset contains 7,828 complete case participants (i.e., no missing) with 14 variables:

-

studyid: Unique identifier -

psu: Pseudo-PSU -

strata: Pseudo-stratum -

weight: Sampling weight -

HICP: HICP (high impact chronic pain, the binary outcome variable) -

sex: Sex -

marital: Marital status -

race: Race/ethnicity -

poverty.status: Poverty status -

diabetes: Diabetes -

high.cholesterol: High cholesterol -

stroke: Stroke -

arthritis: Arthritis and rheumatism -

current.smoker: Current smoker

Let’s see the descriptive statistics of the predictors stratified by the outcome variable (HICP).

Descriptive statistics

# Predictors

predictors <- c("sex", "marital", "race", "poverty.status",

"diabetes", "high.cholesterol", "stroke",

"arthritis", "current.smoker")

# Table 1 - Unweighted

#tab1 <- CreateTableOne(vars = predictors, strata = "HICP",

# data = dat.analytic, test = F)

#print(tab1, showAllLevels = T)

tbl_summary(data = dat.analytic, include = predictors,

by = HICP, missing = "no") %>%

modify_spanning_header(c("stat_1", "stat_2") ~ "**HICP**")| Characteristic |

HICP

|

|

|---|---|---|

|

0 N = 6,8471 |

1 N = 9811 |

|

| sex | ||

| Female | 3,841 (56%) | 623 (64%) |

| Male | 3,006 (44%) | 358 (36%) |

| marital | ||

| Never married | 444 (6.5%) | 60 (6.1%) |

| Married/with partner | 3,183 (46%) | 379 (39%) |

| Divorced/separated | 1,252 (18%) | 198 (20%) |

| Widowed | 1,968 (29%) | 344 (35%) |

| race | ||

| White | 5,455 (80%) | 756 (77%) |

| Black | 606 (8.9%) | 99 (10%) |

| Hispanic | 431 (6.3%) | 79 (8.1%) |

| Others | 355 (5.2%) | 47 (4.8%) |

| poverty.status | ||

| <100% FPL | 543 (7.9%) | 176 (18%) |

| 100-200% FPL | 1,520 (22%) | 307 (31%) |

| 200-400% FPL | 2,309 (34%) | 309 (31%) |

| 400%+ FPL | 2,475 (36%) | 189 (19%) |

| diabetes | 1,275 (19%) | 315 (32%) |

| high.cholesterol | 3,602 (53%) | 633 (65%) |

| stroke | 527 (7.7%) | 146 (15%) |

| arthritis | 3,226 (47%) | 769 (78%) |

| current.smoker | 619 (9.0%) | 123 (13%) |

| 1 n (%) | ||

Weight normalization

Now, we will fit the LASSO model for predicting binary HICP with the listed predictors. Note that we are not interested in the statistical significance of the \(\beta\) coefficients. Hence, not utilizing PSU and strata should not be an issue in this prediction problem. However, we still need to use sampling weights to get population-level predictions. Large weights are usually problematic, particularly with model evaluation. One way to solve the problem is weight normalization (Bruin 2023).

# Normalize weight

dat.analytic$wgt <- dat.analytic$weight *

nrow(dat.analytic)/sum(dat.analytic$weight)

# Weight summary

summary(dat.analytic$weight)

#> Min. 1st Qu. Median Mean 3rd Qu. Max.

#> 243 1521 2604 2914 3791 14662

summary(dat.analytic$wgt)

#> Min. 1st Qu. Median Mean 3rd Qu. Max.

#> 0.08339 0.52198 0.89365 1.00000 1.30109 5.03175

# The weighted and unweighted n are equal

nrow(dat.analytic)

#> [1] 7828

sum(dat.analytic$wgt)

#> [1] 7828Split-sample

Let us create our training and test data using the split-sample approach. We created 70% training and 30% test data for our example.

set.seed(604001)

dat.analytic$datasplit <- rbinom(nrow(dat.analytic),

size = 1, prob = 0.7)

table(dat.analytic$datasplit)

#>

#> 0 1

#> 2343 5485

# Training data

dat.train <- dat.analytic[dat.analytic$datasplit == 1,]

dim(dat.train)

#> [1] 5485 16

# Test data

dat.test <- dat.analytic[dat.analytic$datasplit == 0,]

dim(dat.test)

#> [1] 2343 16Regression formula

Let’s us define the regression formula:

LASSO for Surveys

Now, we will fit the LASSO model for our survey data. Here are the steps:

- We will fit 5-fold cross-validation on the training data to find the value of lambda that gives minimum prediction error. We will incorporate sampling weights in the model to account for survey data.

- Fit LASSO on the training with the optimum lambda from the previous step. Incorporate sampling weights in the model to account for survey data.

- Calculate predictive performance (e.g., AUC) on the test data.

Data in matrix

To perform LASSO with the glmnet package, we need to set the predictors in the data.matrix format and outcome variable as a vector.

Let us see the few rows of the data:

head(X.train)

#> sexMale maritalMarried/with partner maritalDivorced/separated maritalWidowed

#> 12 1 1 0 0

#> 13 1 0 1 0

#> 16 0 0 1 0

#> 42 0 0 0 1

#> 63 0 0 0 1

#> 65 0 0 0 1

#> raceBlack raceHispanic raceOthers poverty.status100-200% FPL

#> 12 0 0 0 0

#> 13 0 0 0 0

#> 16 1 0 0 0

#> 42 0 0 0 0

#> 63 0 0 0 0

#> 65 0 1 0 1

#> poverty.status200-400% FPL poverty.status400%+ FPL diabetesYes

#> 12 1 0 0

#> 13 0 1 0

#> 16 1 0 0

#> 42 0 1 0

#> 63 1 0 0

#> 65 0 0 1

#> high.cholesterolYes strokeYes arthritisYes current.smokerYes

#> 12 0 0 1 0

#> 13 0 0 1 0

#> 16 1 0 1 0

#> 42 1 0 0 0

#> 63 0 0 0 0

#> 65 1 0 1 0As we can see, factor predictors are coded into dummy variables. It is important to note that the continuous predictors should be standardized. glmnet does this by default. Next, we will use the glmnet function to fit the LASSO model.

In glmnet function, alpha = 1 for the LASSO, alpha = 0 for the ridge, and setting alpha to some value between 0 and 1 is the elastic net model.

Find best lambda

Now, we will use k-fold cross-validation with the cv.glmnet function to find the best lambda value. In this example, we choose k = 5. Note that we must incorporate sampling weight to account for survey data.

# Find the best lambda using 5-fold CV

fit.cv.lasso <- cv.glmnet(x = X.train, y = y.train,

nfolds = 5, alpha = 1,

family = "binomial",

weights = dat.train$wgt)

fit.cv.lasso

#>

#> Call: cv.glmnet(x = X.train, y = y.train, weights = dat.train$wgt, nfolds = 5, alpha = 1, family = "binomial")

#>

#> Measure: Binomial Deviance

#>

#> Lambda Index Measure SE Nonzero

#> min 0.001355 43 0.6856 0.01905 12

#> 1se 0.020128 14 0.7036 0.01446 5We can also plot all the lambda values against the deviance (i.e., prediction error).

The lambda value that has the lowest deviance is 0.0013555. Our next step is to fit the LASSO model with the best lambda. Again, we must incorporate sampling weight to account for survey data.

LASSO with best lambda

# Fit the model on the training set with optimum lambda

fit.lasso <- glmnet(x = X.train, y = y.train,

alpha = 1, family = "binomial",

lambda = fit.cv.lasso$lambda.min,

weights = dat.train$wgt)

fit.lasso

#>

#> Call: glmnet(x = X.train, y = y.train, family = "binomial", weights = dat.train$wgt, alpha = 1, lambda = fit.cv.lasso$lambda.min)

#>

#> Df %Dev Lambda

#> 1 12 9.68 0.001355Let’s check the coefficients from the model:

# Intercept

fit.lasso$a0

#> s0

#> -2.491484

# Beta coefficients

fit.lasso$beta

#> 15 x 1 sparse Matrix of class "dgCMatrix"

#> s0

#> sexMale -0.009832818

#> maritalMarried/with partner .

#> maritalDivorced/separated .

#> maritalWidowed 0.041111308

#> raceBlack -0.064853067

#> raceHispanic -0.037985160

#> raceOthers .

#> poverty.status100-200% FPL -0.268494032

#> poverty.status200-400% FPL -0.602097419

#> poverty.status400%+ FPL -1.052635980

#> diabetesYes 0.369667918

#> high.cholesterolYes 0.299475863

#> strokeYes 0.449050679

#> arthritisYes 1.241288036

#> current.smokerYes 0.253439388As we can see, the coefficient is not shown for some predictors. This is because the LASSO model shrunk the coefficient to zero. In other words, these predictors were dropped entirely from the model because they were not contributing enough to predict the outcome. next, we will use the final model to make predictions on new observations or our test data.

Model performance

Now, we will calculate the model performance measures such as AUC, calibration slope, and Brier score Christodoulou et al. (2019). We will incorporate sampling weights to get population-level estimates.

Steyerberg EW, Vickers AJ, Cook NR, Gerds T, Gonen M, Obuchowski N, Pencina MJ, Kattan MW. Assessing the performance of prediction models: a framework for some traditional and novel measures. Epidemiology (Cambridge, Mass.). 2010;21(1):128. DOI: 10.1097/EDE.0b013e3181c30fb2

Steyerberg EW, Vergouwe Y. Towards better clinical prediction models: seven steps for development and an ABCD for validation. European heart journal. 2014;35(29):1925-31. DOI: 10.1093/eurheartj/ehu207

Christodoulou E, Ma J, Collins GS, Steyerberg EW, Verbakel JY, Van Calster B. A systematic review shows no performance benefit of machine learning over logistic regression for clinical prediction models. Journal of clinical epidemiology. 2019;110:12-22. DOI: 10.1016/j.jclinepi.2019.02.004

Area under the curve (AUC) is a measure of discrimination or accuracy of a model. A higher AUC is better. An AUC value of 1 is considered a perfect prediction, while an AUC value of 0.50 is no better than a coin toss. In practice, AUC values of 0.70 to 0.80 are considered good, and those \(>0.80\) are considered very good.

Calibration is defined as the agreement between observed and predicted probability of the outcome. In this exercise, we will estimate the calibration slope as a measure of calibration. A calibration slope of 1 reflects a well-calibrated model, a calibration slope less than 1 indicates overfitting and greater than 1 indicates underfitting of the model.

The Brier score is a measure of overall performance. The Brier score can range from 0 to 1 and is similar to the mean squared error. A lower Brier score value (closer to 0) indicates a better model.

Random Forest for Surveys

Now, we will fit the random forest model for predicting binary HICP with the listed predictors. Here are the steps for fitting the model:

- Fit random forest model on the training set to find the value of the hyperparameters (number of trees, number of predictors to split at in each node, and minimal node size to split at) that gives minimum prediction error. Incorporate sampling weights in the model to account for survey data.

- Grid-search with out-of-sample error approach is widely used in the literature. In this approach, we create a data frame from all combinations of the hyperparameters and check which combination gives the lowest out-of-sample error.

- Fit the random forest model on the training with the selected hyperparameters from the previous step. Incorporate sampling weights in the model to account for survey data.

- Calculate predictive performance (e.g., AUC) on the test data.

Formula

We will use the same formula defined above.

Hyperparameter tuning

For tuning the hyperparameters, let’s use the grid search approach.

# Grid with 1000 models - huge time consuming

#grid.search <- expand.grid(mtry = 1:10, node.size = 1:10,

# num.trees = seq(50,500,50),

# oob_error = 0)

# Grid with 36 models as an exercise

grid.search <- expand.grid(mtry = 5:7, node.size = 1:3,

num.trees = seq(200,500,100),

oob_error = 0)

head(grid.search)Now, we will fit the random forest model with the selected grids. We will incorporate sampling weight as the case weight in the ranger function.

## Calculate prediction error for each grid

for(ii in 1:nrow(grid.search)) {

# Model on training set with grid

fit.rf.tune <- ranger(formula = Formula,

data = dat.train,

num.trees = grid.search$num.trees[ii],

mtry = grid.search$mtry[ii],

min.node.size = grid.search$node.size[ii],

importance = 'impurity',

case.weights = dat.train$wgt)

# Add Out-of-bag (OOB) error to each grid

grid.search$oob_error[ii] <- sqrt(fit.rf.tune$prediction.error)

}

head(grid.search)Let’s check which combination of hyperparameters (number of trees, number of predictors to split at in each node, and minimal node size to split at) gives minimum prediction error.

Model after tuning

Now, we will fit the random forest model with the tuned hyperparameters.

# Fit the model on the training set

fit.rf <- ranger(formula = Formula,

data = dat.train,

case.weights = dat.train$wgt,

probability = T,

num.trees = grid.search$num.trees[position],

min.node.size = grid.search$node.size[position],

mtry = grid.search$mtry[position],

importance = 'impurity')

# Fitted random forest model

fit.rf

#> Ranger result

#>

#> Call:

#> ranger(formula = Formula, data = dat.train, case.weights = dat.train$wgt, probability = T, num.trees = grid.search$num.trees[position], min.node.size = grid.search$node.size[position], mtry = grid.search$mtry[position], importance = "impurity")

#>

#> Type: Probability estimation

#> Number of trees: 300

#> Sample size: 5485

#> Number of independent variables: 9

#> Mtry: 5

#> Target node size: 3

#> Variable importance mode: impurity

#> Splitrule: gini

#> OOB prediction error (Brier s.): 0.1110941Now, we can use the model to make predictions on our test data.

Model performance

The same as the LASSO model, we can calculate the AUC, calibration slope, and Brier score.

# Logit of the predicted probability

dat.test$pred.rf[dat.test$pred.rf == 0] <- 0.00001

dat.test$pred.rf.logit <- Logit(dat.test$pred.rf)

# Weighted calibration slope

mod.cal <- glm(HICP ~ pred.rf.logit,

data = dat.test,

family = binomial,

weights = wgt)

cal.slope.rf <- summary(mod.cal)$coef[2,1]

cal.slope.rf

#> [1] 0.4977901Variable importance

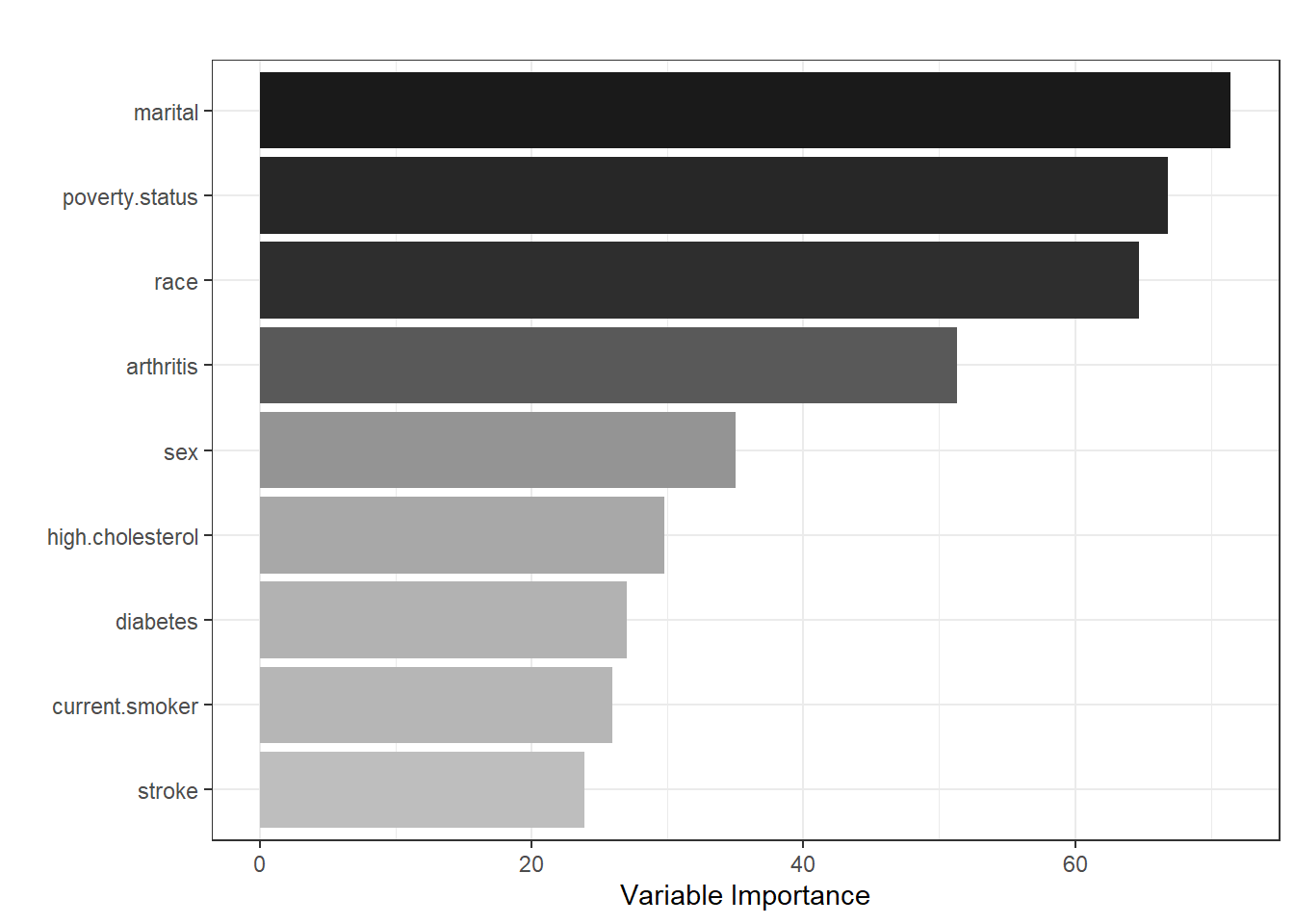

One nice feature of random forest is that we can rank the variables and generate a variable importance plot.

ggplot(

enframe(fit.rf$variable.importance,

name = "variable",

value = "importance"),

aes(x = reorder(variable, importance),

y = importance, fill = importance)) +

geom_bar(stat = "identity",

position = "dodge") +

coord_flip() +

ylab("Variable Importance") +

xlab("") +

ggtitle("") +

guides(fill = "none") +

scale_fill_gradient(low = "grey",

high = "grey10") +

theme_bw()

As per the figure, marital status, poverty status, sex, and arthritis are the most influential predictors in predicting HICP, while stroke is the least important predictor.

Performance comparison

| Model | AUC | Calibration slope | Brier score |

|---|---|---|---|

| LASSO | 0.7662941 | 1.2446448 | 0.0997855 |

| Random forest | 0.6941022 | 0.4977901 | 0.1095384 |